Technology permeates all aspects of our worlds and that of our service users too. When engaging with service users, it is important to include a consideration of their digital lives to establish a genuinely holistic assessment of their circumstances. Doing so may encourage a discussion regarding particular strengths, needs, risks, resilience or protective factors that exist within their online and offline worlds and what support may be required.

It is also important to be mindful that although we may need to consider our safeguarding responsibilities if an adult or child is at risk of harm or in need of protection due to theirs or others’ online activities, this must mirror our Social Care Standards by promoting the autonomy of service users while safeguarding them as far as possible from danger or harm, respecting diversity, upholding choice and working in a person-centred way. This requires critical thinking skills to ensure any support provided is evidence-informed and risk-sensible rather than risk-inflated ‘moral panic’ about potential digital harms. This may be particularly pertinent in situations such as:- ‘screen time rules’, online friendships or dating, gaming/gambling, ‘sharenting’, our views on what is ‘play’ and whether this includes online play and so forth.

Digital boundaries

Unlike traditional face-to-face social work services that are bounded by office hours, home visits or office meetings, the digital world is unbounded by time and space and this may create challenges for service users and practitioners alike. For example, practitioners may face ethical challenges about whether information obtained online is used in safeguarding cases, particularly as it could be faked, inaccurate or outdated. Conversely, service users may use digital platforms to gain support for their situation – this may or may not be respectful of individual social workers or services’. Therefore, it is important to be both mindful of digital boundaries and explore these with our service users in our contracting stages.

What are people doing online?

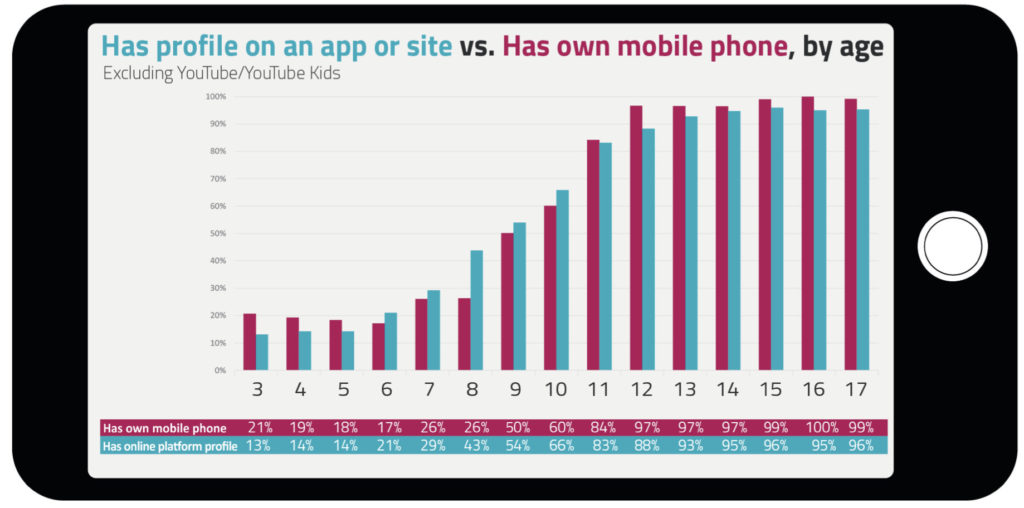

It may not be a surprise that in recent years, the top three sites for global internet traffic worldwide have steadily remained as Google, You Tube and Facebook. This can provide us with a general snapshot of what we are all doing online – creating, consuming, communicating and connecting. The vast majority of people in the UK are online and this includes even our very youngest citizens – 87% of 3 to 4 year olds go online mainly to watch videos on You Tube and 21% of 3 year olds have their own mobile phone! 58% of children aged 3-15 use social media such as YouTube, TikTok and Snapchat and the majority of children report that using social media and messaging sites or apps makes them feel happy most or all of the time.

Click image to view full size

Stranger danger?

The digital landscapes have changed traditional concepts of ‘friends’, as people of all ages may interact with others they do not know “in the real world” on gaming platforms, socials, groups and communities where they share similar interests. This may create value challenges for some, as the fundamental idea of engaging with ‘strangers’ is traditionally discouraged and perceived as potentially dangerous. Whilst it would be prudent to discourage sharing personal information, direct messaging or ‘private chat’ with online ‘strangers’, for many these interactions may be akin to playing in the proverbial online ‘playground’, which is an incredibly popular way for many to enjoy their social time. It is equally important for children, young people and adults who have particular vulnerabilities to be informed about engaging with others online in the same way we would have this discussion in ‘real life’ face-to-face interactions about people they do not know.

Particular concerns

Whilst there are myriad benefits to our digital lives and it is important that we remember that internet users as a whole believe such benefits outweigh the risks, we know there are also concerns that may be overinflated in certain populations. For example, younger adults, aged 18-24, are more likely to encounter hateful, offensive or discriminatory content and older users 55+ are more likely to encounter scams, fraud or phishing. Overall, 62% of internet users aged 13+ have encountered at least one potential harm online in the last four weeks. Considering our work with service users, looked after children are seven times more likely to experience online harms and those within lower socio-economic groups are less digitally confident and unable to identify scams. Certain groups receiving social work support including older people, those from low socio-economic backgrounds and people with disabilities and mental health issues are the most likely to be digitally excluded. There continues to remain a correlation between those within lower socio-economic groups and:-

- Internet access (digital poverty)

- Digital confidence and skills (digital literacy)

- Ability to identify scams (critical thinking skills)

- Understanding search engine advertising, and

- Critical thinking skills regarding truthfulness of online information.

This is as true for service users supported by social workers as it is for anyone else. It’s important to note that offline and online vulnerabilities are correlated (i.e. if you are vulnerable offline you are more likely to be vulnerable online) and as such, some of the people we work with may be exposed harm online and may require your support in navigating all things digital (e.g. see boyd, “It’s complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens”).

Reflective learning exercise

Complete the exercises below and keep a record of your reflections.

Reflective case studies

After reviewing the case studies above, select one or more and take a moment to consider the following questions.

We are always interested in ensuring our resources are valuable tools for the workforce and are keen to hear your feedback, or ideas for future topics which could be included in this resource.